Silently, seamlessly, relentlessly the electrical fairy keeps everything running. Behind the scenes of modern economies, critical industries rely on vast, complex structures. Among them, the electric grid is often described as the largest and most complex machine ever built.

Electricity, once a closed industrial chain, now flows through rooftops and fields, garages and offshore pylons, all the way into homes. As the grid expanded, its architecture evolved to become an Ultra-Large-Scale System, where all components and stakeholders continuously communicate. By sharing real‑time data, interconnected power systems optimize demand response and production. The grid may be strong, but complacency has convinced many that it’s too big to fail. Yet attackers have already noticed the cracks in this vast ecosystem. When the attack surface grows faster than governance and operational practices can adapt, controlling boundaries and coordinating stakeholders becomes increasingly difficult.

In this article, we will explore why the grid’s new external frontier has become its biggest blind spot, and what securing this new “borderless” infrastructure truly requires.

The Nervous System of Modern Economies

Among all critical infrastructures, the power sector stands as one of the most essential (alongside water). It acts as the nervous system of modern economies: constantly sending and receiving information between the grid and the outside world (customers, businesses, hospitals...), and within the grid itself.

Two Currents, One Grid: Energy and Data Flow Both Ways

Unlike any other sector, electricity is the only critical infrastructure that operates simultaneously in two bidirectional dimensions: energy and data. Energy flows no longer originate solely from centralized power plants; distributed energy resources (DER) now inject electricity back into the grid at every voltage level. Data flows are equally bidirectional: smart meters, inverters, IoT gateways, and flexibility platforms exchange commands and telemetry across millions of endpoints.

As a result, the responsibility for maintaining stability is increasingly shared between operators and numerous actors they neither own nor directly supervise. In other critical infrastructures (oil, gas, and water) systems remain structurally centralized: production assets are industrial; supply chains are limited, and control points are few. Electricity is the opposite: its supply chain is sprawling, fragmented, and increasingly shaped by small operators, niche vendors, and households. All of whom send power production and data back into the grid.

The Grid’s Spinal Cord: What DSOs Sense and Control

In the human body, the spinal cord belongs to the central nervous system and transmits information between the brain and the rest of the body. Distribution System Operators (DSOs) play a similar role. In Europe, the “brain” corresponds to the Transmission System Operator (TSO), such as France’s RTE. In North America, this role is fulfilled by Independent System Operators (ISOs) like PJM Interconnection or Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs).

DSOs, like the spinal cord, receive vast amounts of information from field and offshore devices (i.e.: wind turbines, solar panels, sensors, and inverters). In the body, sensory information is analyzed to understand the environment and ensure internal stability. A loss of sensation in your fingertips can signal poor blood circulation or external cold. DSOs rely on data in exactly the same way to sense the state of the grid, detect anomalies early, and maintain safe and stable operation.

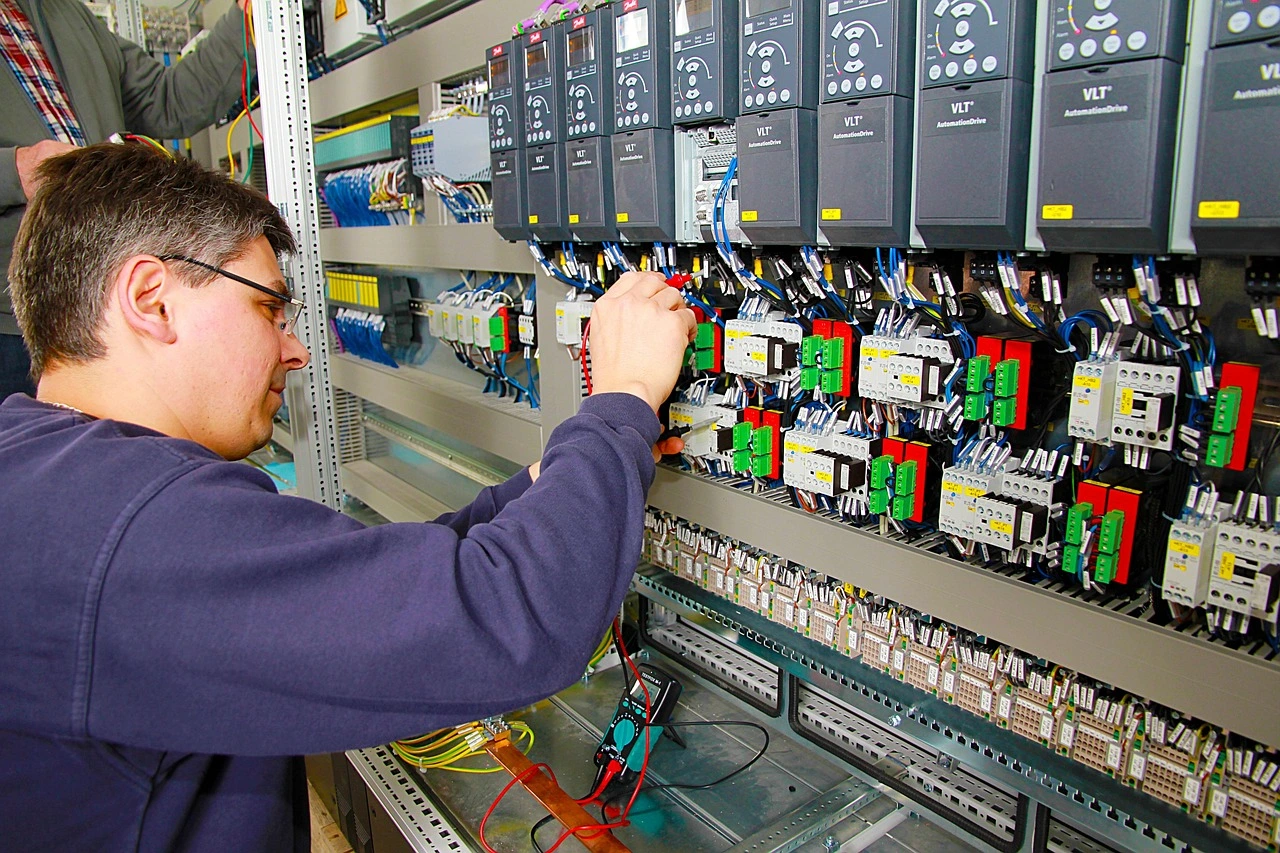

The Many Eyes of the Grid: DSOs and Their Overlapping Information Systems

A DSO’s operational environment is built on a dense layering of information systems, each added over time as the grid grew more digital, more intelligent, and more distributed. These systems are the equivalent of the body’s sensory pathways. Each one captures a different dimension of what is happening deep inside the network, feeding operators with the signals they need to maintain safe and stable operation. In this constantly shifting landscape, maintaining uninterrupted situational awareness is not just an operational requirement. It is the grid’s equivalent of staying alive.

Sensing the Grid: Power industry’s information systems

Among them, the SCADA system remains the central sensory organ. It supervises the real‑time behavior of the grid, gathering measurements from devices spread through substations, feeders, and remote areas. Field equipment sends continuous information on voltage, power flow, breaker position, or fault conditions. SCADA converts these raw signals into meaningful data through transducers and telemetry protocols, delivering them to the human–machine interface where operators interpret, anticipate, and act. It is the closest equivalent to a reflex arc: fast, continuous, and essential to survival.

Alongside SCADA, the Outage Management System adds another layer of perception. It correlates alarms, fault indicators, switching operations, and customer calls to determine where an incident has occurred and how it evolves. By translating scattered signals into a coherent picture, OMS provides the “pain response” of the grid, enabling DSOs to understand disruptions quickly and prioritize restoration work. It also connects to customer‑facing services, offering visibility on failures and repair status.

The Geographic Information System brings spatial intelligence to this ecosystem. GIS organizes and visualizes the entire physical infrastructure of the distribution network: cables, transformers, substations, and distributed energy resources. It allows operators to understand risks in a geographical context, assess the feasibility of integrating new renewable energy assets, and plan maintenance operations with precision. In a sense, GIS acts as the grid’s spatial awareness, allowing the system not only to feel but also to understand where things are happening.

Together, these systems form the eyes, ears, and reflexes of the distribution network. Through them, DSOs monitor load flows, grid status, alarms, and switching operations remotely, coordinating field crews and ensuring that the grid always operates within safe limits.

The blind spots

DSOs’ role spans the stability of daily operations, the fulfillment of electricity demand, and participation in balancing or ancillary service mechanisms. Losing visibility, even for a moment, is not an option. These multiple layers of perception (digital and physical, modern and legacy) form the sensory fabric through which DSOs navigate an increasingly complex and distributed grid.

Smart‑grid DSOs already operate within several layers of protection: domain systems, segmented networks, and strict access controls. Yet attacks keep rising, often beginning with phishing campaigns in corporate IT before pivoting into OT, or exploiting legacy industrial protocols never designed for hostile environments. The result is a stream of signals whose integrity can no longer be taken for granted.

Adversaries increasingly target poorly secured connections to inverters and other DER units, tampering with telemetry or commands to push operators toward harmful actions. They may end up curtailing healthy feeders, dispatching crews unnecessarily, or even triggering unwarranted shutdowns. In a landscape that shifts by the hour, uninterrupted situational awareness is not just a requirement; it is the grid’s equivalent of staying alive. Corrupted signals don’t merely blur the picture—they can steer the hand that acts on it.

And as DSOs navigate multiple environments across IT and OT, poor segmentation can amplify the impact of compromises. A breach that begins at the edge may move inward, exposing billing records, customer data, and sensitive personal information. The more distributed the grid becomes, the more a single weak interface can cascade into a broader operational and informational incident.

Surgical Isolation: Reconciling Security and Visibility.

The more digital the grid becomes, the more DSOs find themselves navigating a delicate tension. Regulations push them toward stricter isolation between systems, while operations demand uninterrupted visibility. In theory, segmentation is essential: separate the critical nerves of the grid from corporate IT, isolate sensitive systems, prevent lateral movement in case of intrusion. In practice, however, a new security layer can obstruct the very signals operators rely on to keep the grid alive.

Prescriptions and Side Effects: When Compliance Meets Reality

Regulators are clear in their expectations, but the operational reality is far messier than regulatory texts acknowledge. NIS2 reinforces the principle of network segmentation across Europe. For DSOs such as Enedis, Article 21 translates into tangible obligations: risk management aligned with security best practices, IT and OT segmentation, and the presence of firewalls between operational systems like SCADA or hardwired annunciator units and the broader corporate environment. These rules are intended to protect the nervous system of the grid from external infection.

However, their application often introduces new frictions inside control centres that are already burdened with complexity. In DSO’s centre, more isolation frequently means more screens, more physical terminals, and more equipment per operator. The trade-offs are financial, human in terms of usability for the end-users, but also environmental. In this context, traditional virtualization approaches like VDI are no options for DSO engineers who can’t afford to lose communication or visibility. VDI dependency on connection brings a risk of disconnection or latency, which may prevent an operator from seeing a crucial alarm.

So how do we secure the grid? The secret recipe.

That’s the one‑billion‑dollar question. Securing the power grid is unlike securing any other system. With DER units stretching the perimeter into homes, rooftops, and private sites, the grid is effectively borderless. Only a handful of DSO engineers see all sides of this landscape, bridging legacy OT systems that remain indispensable and the modern solutions now layered on top of them. Focus becomes the operator’s greatest asset: when you cannot control the threats outside your perimeter, security becomes a matter of protecting the surface you do own and staying flexible where you must.

In a borderless grid, operational security depends on reconciling segmentation, visibility, and usability across an entire ecosystem. And that work begins with empathy. IT and OT teams must understand each other’s priorities, constraints, and rhythms. They need a common vision of what security means—not as a checklist, but as a shared discipline.

The next step is proper segmentation. Each environment must be clearly isolated to prevent propagation, especially for DSOs, who cannot afford lateral movement between operational and corporate domains. Isolation should preserve the anatomy of operations, not fracture it.

Finally, maintenance teams need tools that respect physics, timing, and field reality. Next‑generation virtualization allows them to work from a single device hosting multiple fully isolated environments. One environment handles corporate tasks. Another is reserved for operations, with exclusive access to specific ports or peripherals. Each domain has its own policies, settings, and permissions—while access to OT remains tightly brokered. In practice, this means engineers retain the speed and tools they rely on; companies gain responsiveness; and maintenance teams work with more comfort and confidence.

Inside control centers, the same logic applies. DSOs finally get segmentation that holds: each virtual environment is tied to its own domain and displayed on its own dedicated monitor, without disrupting operators’ preferred layouts or their reflex‑based workflows. Last but not least, Priviledged Access Workstations can enhance security by enforcing controls on who can access systems remotely and when they can do so.

Conclusion: Conciling visibility and security

The power industry is facing a dilemma: regulations tighten internal segmentation, but the true blind spot lies at the periphery, where the nervous system meets the outside world. It is the most tangible example of critical infrastructure whose true resilience is built when architectures are designed to confine risk, when every access point leaves a traceable record, and when security solutions are shaped by the realities of control centres and remote sites, not the other way around. And this is what KERYS Sotware delivers.

We understand that, in a borderless grid, operational security is no longer just an internal governance issue. It is the art of preserving visibility, enforcing segmentation, and enabling people to do their jobs without losing the signals that keep the grid alive.

Does it sound too good to be true? Let us show you how we do it.